A beach is perhaps the ultimate place for forgetting to happen. It routinely erases memories almost as soon as they are made, whether foot prints, sand castles or anything left within reach of its ritualistically grabby tide. The oscillating water line is completely impartial and uninterested in politics and stories, or human definitions of “right” or “wrong”. It just stretches out and grabs, with an indiscriminate and nonnegotiable reach, whatever is there for it to grab. With enough time it will wash clean even the most horrible of happenings and leave the same blank, beautiful and impressionable sand behind with no record of what was once there.

The tide imposes its will upon it all, insistently pushing the present as quickly as possible into the past. Unlike a forest that might grow around a relic, making any history permanent, or the earth that might preserve a story in a hidden place underfoot, on the beaches of Normandy in France, it is only human will that can do the work to keep that history present.

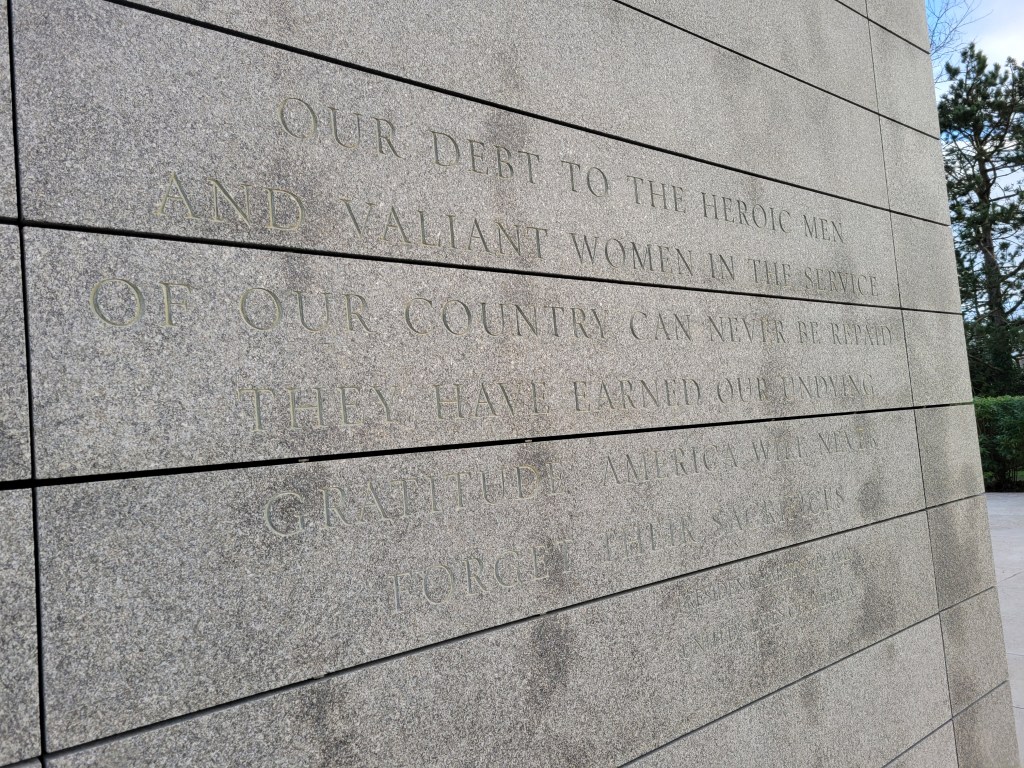

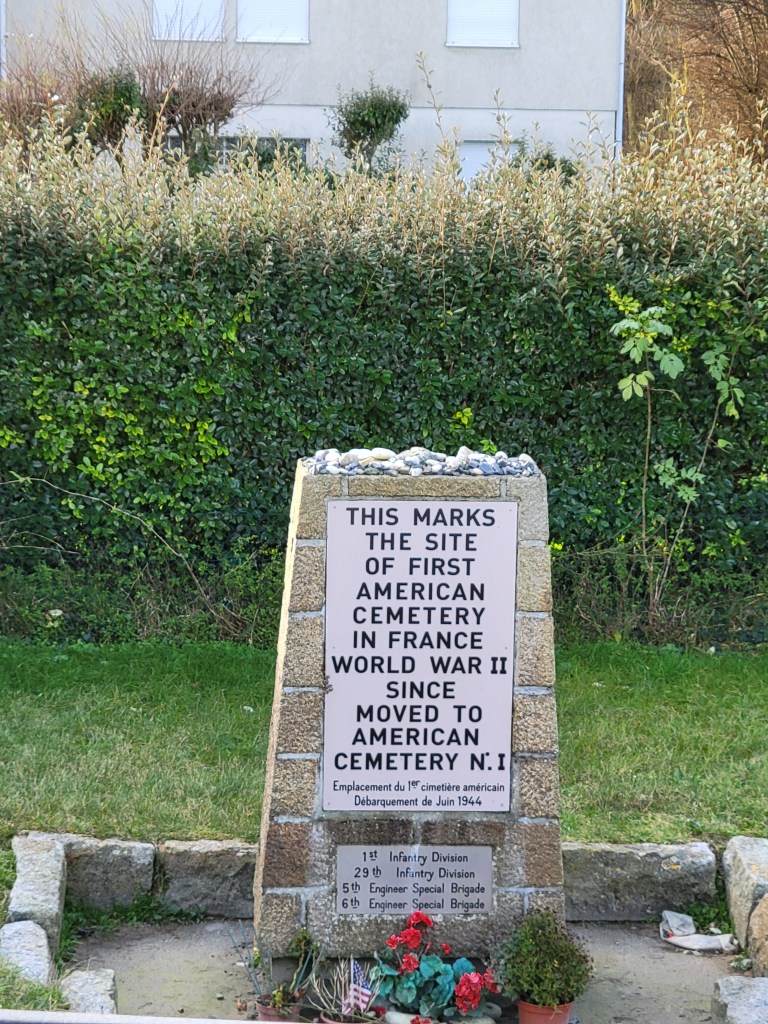

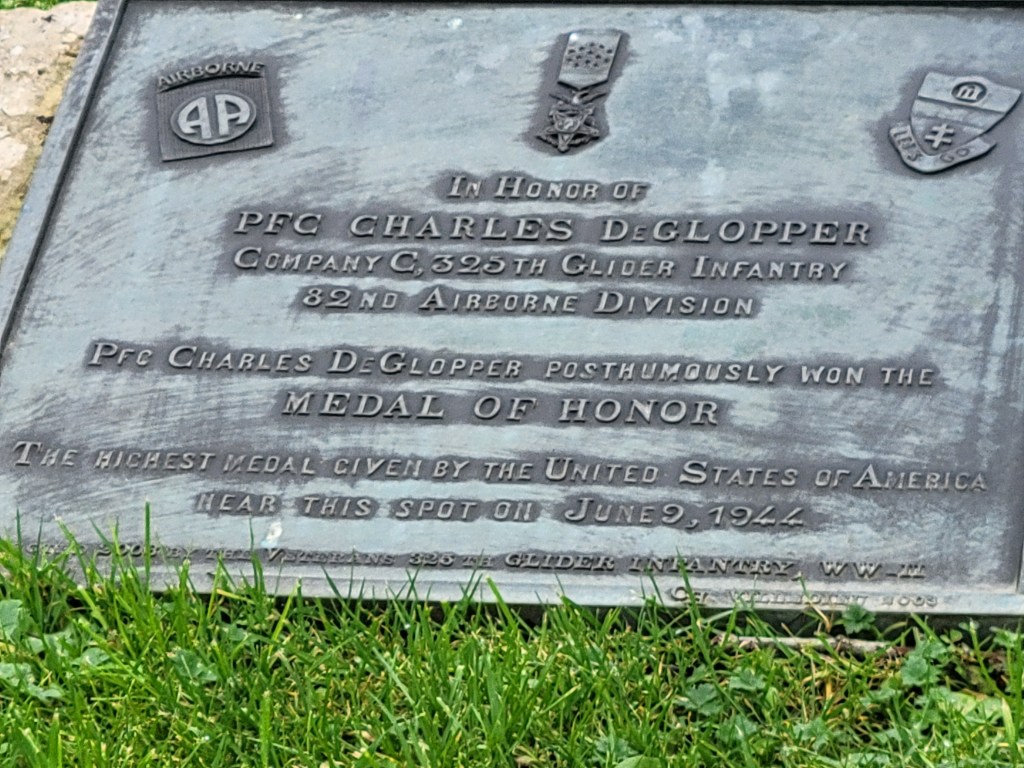

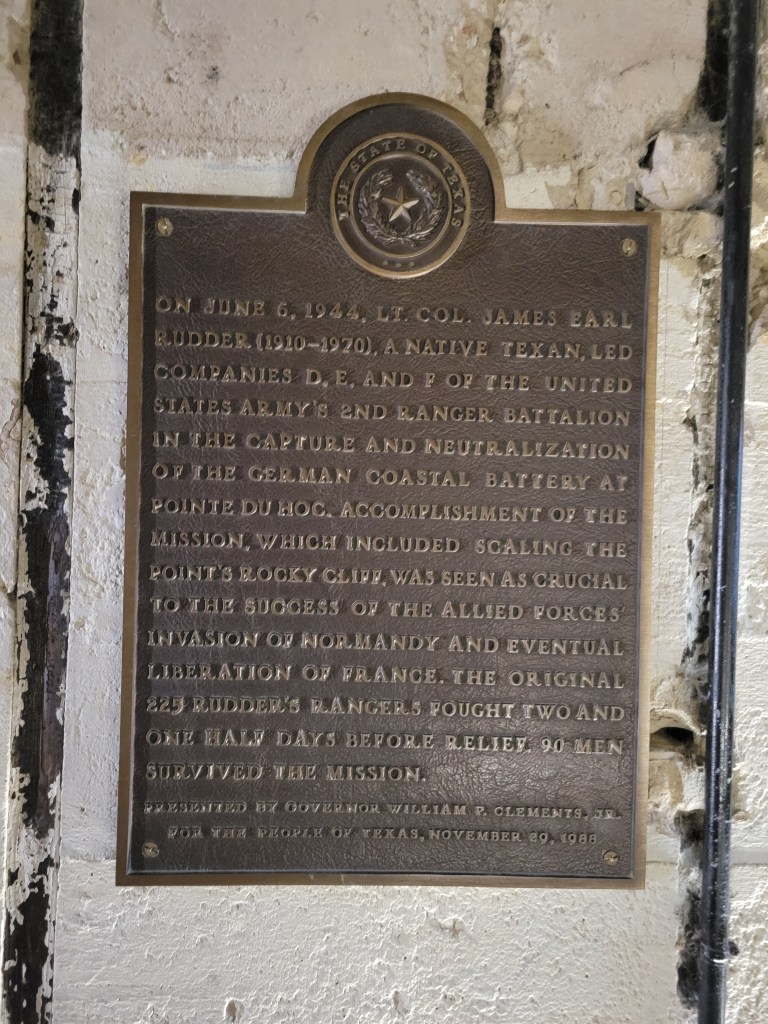

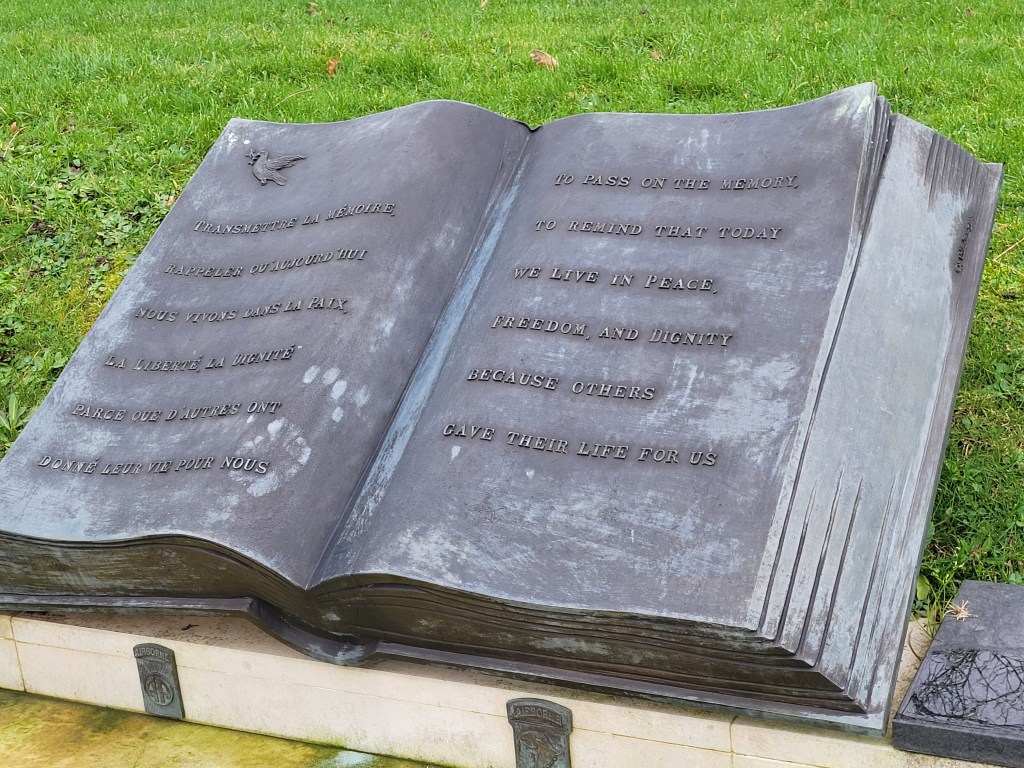

And humanity has taken up that charge. Monuments, museums, cemeteries and tours are all amply available to jog the memory and keep one from being lulled into forgetting what happened here on this otherwise peaceful beach and the various other spots along the coast and inland.

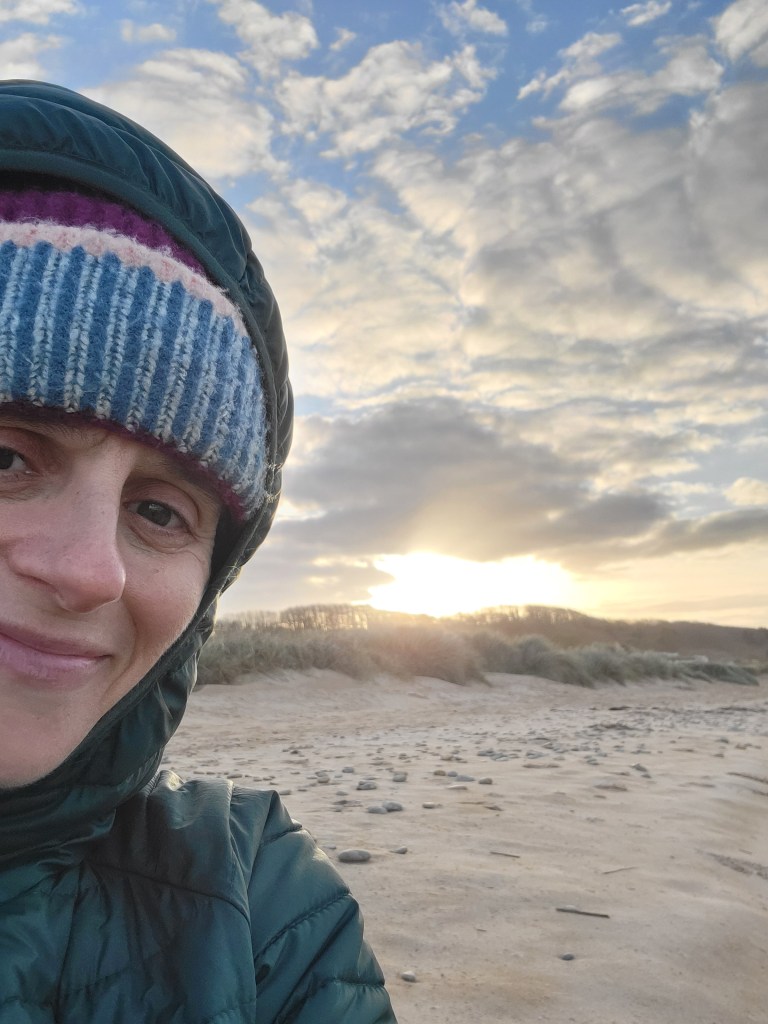

It is an internal battle in my own mind to force those images of the past on top of a place that is as beautiful and tranquil as any beach I’ve been on. Luckily, there is a refreshing chill in the air helping me keep from sinking totally into a relaxed comfort.

Having chosen a chilly but lovely December day to visit Normandy, I was lucky to have privacy, solitude and a complete absence of the long lines of summer time. It was easy to get a last minute hotel. I would love to return for the festivities that will fill the beaches, the parking lots and the hotels this June at the 80th anniversary of D-Day, but today, I got to enjoy the experience in the quiet embrace of relative solitude.

There were a few moments on the beach when I couldn’t see another soul in either direction. The sky was so beautiful as it woke up the neighborhoods just behind the shore, I could barely stop taking pictures. One after the other, each more beautiful than the one before.

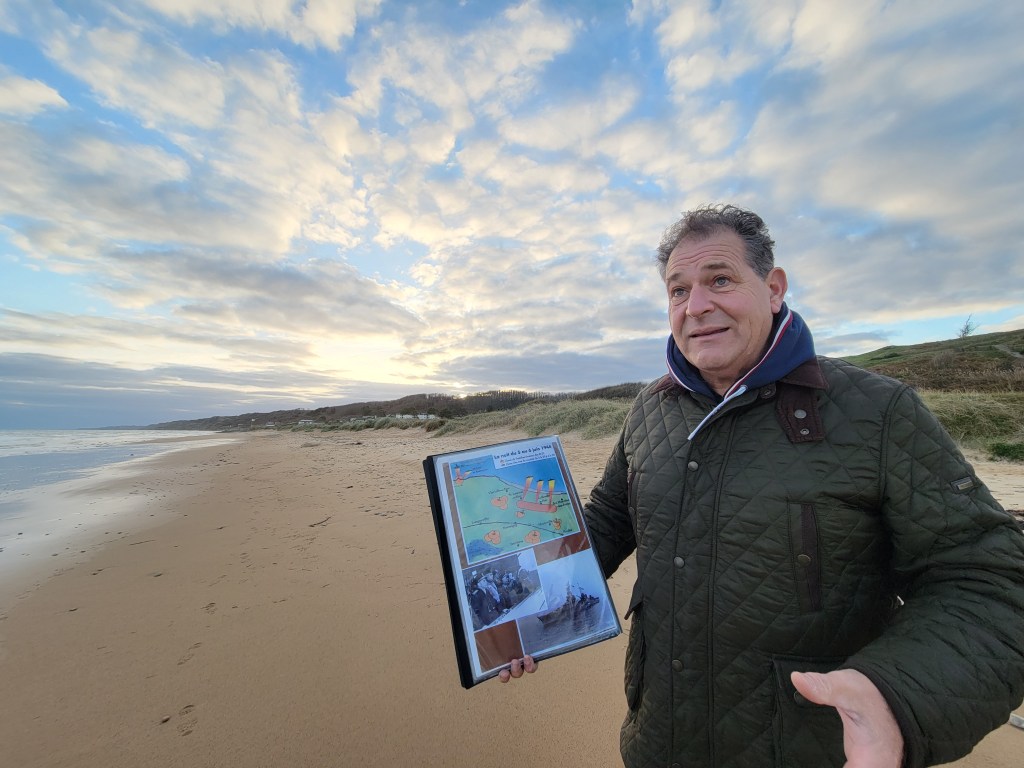

After my tour guide, Olivier, gave me a great presentation on the events of the past in wondeful detail on this gorgeous, frigid morning on codename “Omaha” Beach, he left me to my own quiet reflections.

If it weren’t for the plaque nailed upon a stone in homage to the medics that laid their lives on the line in the effort to save as many as they could, a stone big enough and deeply entrenched enough in the earth to lay its claim to a permanent spot on the beach despite the tide beating upon it with rhythmic persistance, I would have had no evidence of the gruesomeness, heroism and massive efforts of thousands of ships and men that once filled the seas at this shore.

There were moments that I was so lulled by the simple pleasure of sitting on a beautiful beach that I found myself feeling like my own mind was just a sandcastle itself, slowly getting washed back to a flat uneventful surface.

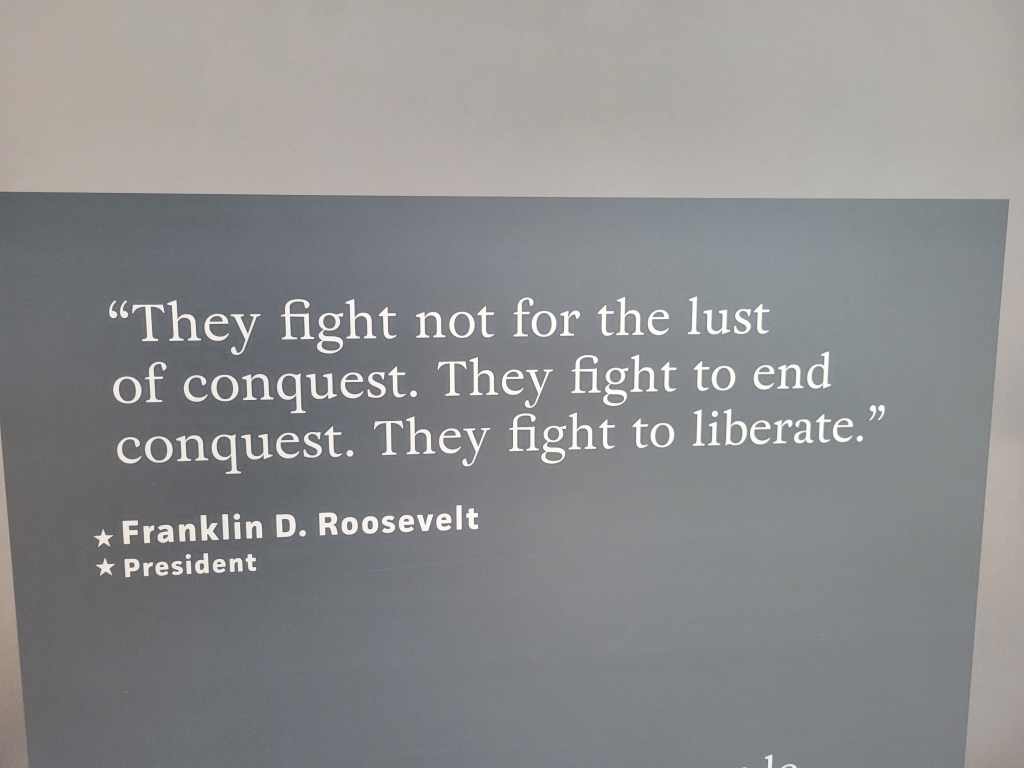

But, like all the monuments built all over this coastline and inland, what I was there for was firmly planted in the front of my mind and the emotions started stirring and flowing. I have thought about this beach countless times throughout my life. It has, for me, been the most jaw dropping of events to comprehend amidst the many hard to really imagine elements and happenings of World War II. The amount of courage and strength that thousands of young men, boys really, displayed to even be in those boats let alone run out of them – I can hardly comprehend. I have lived my life not only in a state of unending gratitude but total and complete awe thinking about that fact and that moment. What have I been willing or able to compel myself to do simply because it was the right thing to do? What have I done because somewhere in a land far away, a madman was on a murderous rampage and I was going to put myself in such dire circumstances to stop it? Well, to the second question, nothing. To the first, as much as I could, but nothing that even approximates an equal dedication, courage and self-sacrifice. I have always tried to do what I can to be a decent moral person living in a time where just knowing what is and is not the decent thing is much more complex and nuanced than such a harsh reality as the one of that time and the choice to be on this beach during it. Many life issues have grey areas, multiple valid viewpoints and nuances to consider. This one was fairly black and white. Or, at least as my world view goes. But even then, until Pearl Harbor, there was as much debate and multiple perspectives and division amongst them as any since. I am reading a book now called Those Angry Days that describes the voracious debate that raged in America about whether or not to enter the war when it started in Europe in 1939. As I read it, I find myself empathizing with different arguments and seeing similarities in other seemingly intractable debates throughout history since and of today, where there is often not an issue of who is right and who is wrong, but an issue of how well or differently the situation is or is not understood and what matters most to each person. Isolationists did not want to sacrifice their American sons in a bloody war happening far away. Interventionists ALSO did not want American sons to die and so horribly, but they thought stopping that madman was more morally and practically “worth” such an awful cost or at least necessitated it. This once complex and nuanced equation was eventually made horrifically simple as events progressed. The stakes eventually became clearly as high as they could possibly be. More and more opinions fell into the interventionist camp as the true gruesome vision of those on the assault became more and more clear. By the time Paris fell, more and more Americans began to see how horrific and unambiguous it all was. And after Pearl Harbor was hit and the Americam illusion of being “far away” from the reaches of such conquering, violent hungers was destroyed, overnight, the complexity of the debate instantaneously shrank to zero and an entire country, our entire country’s emotion was simplified into one united and distinct voice. I do hold out hope that such empassioned unity does not necessitate only such horrific disaster to take shape, but I am glad that when such a darkened motive did force its will upon the world, it did. So the sacrifices were eventually decided to be “worth it”, if anything really could be “worth” such costs, not just by the country, but by those heroic men and women themselves that made the decision, enthusiastically and unequivocally, to enlist and put their own lives wholeheartedly on the line so that we could live ours in peace and freedom. None knew at the moment of enlisting that they would end up on those boats, about to hurl themselves forward into utter and brutal disaster, but they knew they were walking into something where death would be waiting around every corner. The stakes were as high as they could be and so were the costs of almost any decision made. But they made their decisions and they made them decisively.

And, in the early morning of June 6, 1944, that included the decision to run up on that beach.

A seemingly very different beach than the one I was sitting on, though in fact the very same one.

The same beach that has no vote on what does or does not happen upon it. The tide just goes in and then goes out, pushing and pulling, as it has for eons upon eons and will for as many more to come.

For me personally, being here was a very special way to close up this first round of writing my musical, which, as a friend recently said to me, is my own love letter to a generation that threw itself in harms way to preserve for posterity a way of life that I treasure and in the case of my own ancestry, to preserve posterity itself. It is my own way of expressing my acknowledgement and my gratitude. Being there physically was a meaningful way to close up the task.

A lot of men died on that beach in the most brutal of ways. As many men were given memories that would haunt them for all of their remaining days.

Sitting on that beach, alive, well and very much thriving, I felt a very strong awareness that all those boys, those men, saved my life when they gave theirs. They didn’t do it for me personally, but for the idea of me, for all that get to enjoy a life of freedom. I don’t know that its ever possible that I can do anything to make such a sacrifice truly “worth it”, but I do feel, the least I could attempt to do to contribute to that impossible task is to treasure my life everyday, to savor the miracle and gift they gave me of being alive and hopefully, in my own way, to try and make my own contribution to a good world.

The beach maybe has forgotten, but I, among many, certainly haven’t. So, I got to sit on that indifferent sand and say thank you.

And as soon as I left, I know that beach forgot me too.

There is much more to report on of life on the “road” (more like in the air, on the train and sometimes, yes, on the road), but I think I’ll save it for another post.